In a fascinating survey taken at the start of the University of Derby’s ‘Dementia’ MOOC, using Canvas, where 775 learners were asked whether they expected to fully engage with the course, 477 said yes but 258 stated that they did NOT INTEND TO COMPLETE. This showed that people come to MOOCs with different intentions. In fact, around 35% of both groups completed, a much higher level of completion that the vast majority of MOOCs. They bucked the trend.

Now much is made of dropout rates in MOOCs, yet the debate is usually flawed. It is a category mistake to describe people who stop at some point in a MOOC as ‘dropouts’. This is the language of institutions. People drop out of institutions, ‘University dropouts', not open, free and online experiences. I’m just amazed that many millions have dropped in.

So let’s go back to that ‘Dementia’ MOOC, where 26.29% of those that enroled never actually did anything in the course. These are the window-shoppers and false starters. False starters are common in the consumer learning market. For example, the majority of those who buy language courses, never complete much more than a small portion of the course. And in MOOCs, many simply have a look, often just curious, others want a brief taster, just an introduction to the subject, or just some familiarity with the topic, and further in, many find the level inappropriate or, because they are NOT 18 year old undergraduates, find that life (job, kids etc.) make them too busy to continue. For these reasons, many, myself included, have long argued that course completion is NOT the way to judge a MOOC (Clark D. 2013, Ho A. et al, 2014; Hayes, 2015).

Course completion may make sense when you have paid up front for your University course and made a huge investment in terms of money, effort, moving to a new location and so on. Caplan rightly says that 'signalling' that you attended a branded institution explains the difference. In open, free and online courses there is no such commitment, risks and investments. The team at Derby argue for a different approach to the measurement of the impact of MOOCs, based not on completion but meaningful learning. This recognises that the diverse audience want and get different things from a MOOC and that this has to be recognised. MOOCs are not single long-haul flights, they are more like train journeys where some people want to get to the end of the line but most people get on and off along the way.

Many of the arguments around course completion in MOOCs are,

I have argued, category mistakes, based on a false comparison with traditional

HE, semester-long courses. We should not, of course, allow these arguments to

distract us from making MOOCs better, in the sense of having more sticking

power for participants. This is where things get interesting, as there have

been some features of recent MOOCs that have caught my eye as providing higher

levels of persistence among learners. The University of Derby ‘Dementia’ MOOC,

full title ‘Bridging the Dementia Divide: Supporting People Living with

Dementia’ is a case in point.

1. Audience sensitive

MOOC

learners are not undergraduates who expect a diet of lectures delivered

synchronously over a semester. They are not at college and do not want to

conform to institutional structures and timetables. It is unfortunate that many

MOOC designers treat MOOC learners as if they were physically (and

psychologically) at a University – they are not. They have jobs, kids, lives,

things to do. MOOC designers have to get out of their institutional thinking

and realize that their audience often has a different set of intentions and needs.

The new MOOCs need to be sensitive to learner needs.

2. Make all material available

To be

sensitive to a variety of learners (see why course completion is a wrong-headed

measure), the solution is to provide flexible approaches to learning within a

MOOC, so that different learners can take different routes and approaches. Some

may want to be part of a ‘cohort’ of learners and move through the course with a

diet of synchronous events but many MOOC learners are far more likely to be driven

by interest than paper qualifications, so make the learning accessible from the

start. Having materials available from day one allows learners to start later

than others, proceed at their own rate and, importantly, catch up when they

choose. This is in line with real learners in the real world and not

institutional learning.

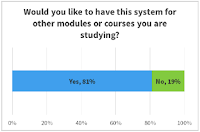

2. Modular

The idea of

a strictly linear diet of lectures and learning should also be eschewed, as

different learners want different portions of the learning, at different times.

A more modular approach, where modules are self-contained and can be taken in

any order is one tactic. Adaptive MOOCs, using AI software that guides learners

through content on the basis of their needs, is another. 6.16% of the dementia

MOOCs didn’t start with Module 1.

This tracked data shows that some completed the

whole course in one day, others did a couple of modules on one day, many did

the modules in a different order, some went through in a linear and measured

fashion. Some even went backwards. The lesson here is that the course needs to

be designed to cope with these different approaches to learning, in terms of

order and time. This is better represented in this state diagram, showing the different

strokes for different folks.

Each circle is a module containing the number of

completions. Design for flexibility.

3. Shorter

MOOC

learners don’t need the 10-week semester structure. Some want much shorter and

faster experiences, others medium length and some longer. Higher Education is

based on an agricultural calendar, with set semesters that fit harvest and

holiday patterns. The rest of the world does not work to this pre-industrial

timetable. In the Derby Dementia

MOOC, there is considerable

variability on when people did their learning. Many took less that the six

weeks but that did not mean they spent less time on the course, Many preferred concentrated

bouts of longer learning than the regular once per week model that many MOOCs

recommend or mandate. Others did the week-by-week learning. We have to

understand that learning for MOOC audiences is taken erratically and not always

in line with the campus model. We need to design for this.

4. Structured and unstructured

I personally find the drip-feed, synchronous, moving through

the course with a cohort, rather annoying and condescending. The evidence in

the Dementia MOOC suggests that there was more learner activity in unsupported

periods than supported periods. This shows a considerable thirst for doing things

at your own pace and convenience, than that mandated by synchronous, supported

courses. Nevertheless, this is not an argument for a wholly unstructured

strategy. This MOOC attracted a diverse set of learners and having both

structured and unstructured approach brought the entire range of learners

along.

You can see that the learners who experienced the structured

approach of live Monday announcement by the lead academic, a Friday wrap-up

with a live webinar, help forum and email query service was a sizeable group in

any one week. Yet the others, who learnt without support were also substantial

in every week. This dual approach seems ideal, appealing to an entire range of

learners with different needs and motivations.

5. Social not necessary

Many have

little interest in social chat and being part of a consistent group or cohort.

One of the great MOOC myths is that social participation is a necessary

condition for learning and/or success. Far too much is made of ‘chat’ in MOOCs,

in terms of needs and quality. I’m not arguing for no social components in

MOOCs, only claiming that the evidence shows that they are less important than

the ‘social constructivist’ orthodoxy in design would suggest. In essence, I’m

saying it is desirable but not essential. To rely on this as the essential pedagogic

technique, is, in my opinion, a mistake and is to impose an ideology on

learners that they do not want.

6. Adult

content

In line

with the idea of being sensitive to the needs of the learners, I’ve found too

many rather earnest, talking heads from academics, especially the cosy chats,

more suitable to the 18 year-old undergraduate, than the adult learner. You need

to think about voice and tone, and avoid second rate PhD research and an

over-Departmental approach to the content. I’m less interested in what your

Department is doing and far more interested in the important developments and

findings, at an international level in your field. MOOC learners have not

chosen to come to your University, they’ve chosen to study a topic. We have to

let up on being too specific in content, tone and approach.

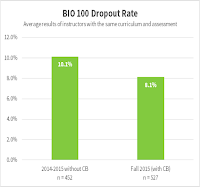

7. Content as a driver

In another interesting study of MOOCs, the researchers found that stickiness was highly correlated to the quality of the 'content'. This contradicts those who believe that the primary driver in MOOCs is social. They found that the learners dropped out if they didn't find the content appropriate, or of the right quality and good content turns out to be a primary driver for perseverance and completion, as their stats show.

8. Badges

In another interesting study of MOOCs, the researchers found that stickiness was highly correlated to the quality of the 'content'. This contradicts those who believe that the primary driver in MOOCs is social. They found that the learners dropped out if they didn't find the content appropriate, or of the right quality and good content turns out to be a primary driver for perseverance and completion, as their stats show.

8. Badges

The

Dementia MOOC had six independent, self-contained sections, each with its own

badge for completion, and each can be taken in any order, with an overall badge

for completion. These partial rewards for partial completion proved valuable.

It moves us away from the idea that certificates of completion are the way we

should judge MOOC participation. In the Dementia MOOC 1201 were rewarded with

badges against 527 completion certificates.

9. Demand driven

MOOCs are made for all sorts of reasons, marketing, grant applications, even whim - this is supply led. Yet the MOOCs market has changed dramatically, away from representing the typical course offerings in Universities, towards more vocational subjects. This is a good thing, as the providers are quite simply reacting to demand. Before making your MOOC, do some marketing, estimate the size of your addressible audince and tweak your marketing towards that audience. Tis is likely to resultin a higher number of participants, as well as higher stickiness.

10. Marketing

If there's one thing that will get you more participants and more stickiness, it's good marketing. Yet academic institutions are often short of htese skills or see it as 'trade'. This is a big mistake. Marketing matters, it is a skill and need a budget.

9. Demand driven

MOOCs are made for all sorts of reasons, marketing, grant applications, even whim - this is supply led. Yet the MOOCs market has changed dramatically, away from representing the typical course offerings in Universities, towards more vocational subjects. This is a good thing, as the providers are quite simply reacting to demand. Before making your MOOC, do some marketing, estimate the size of your addressible audince and tweak your marketing towards that audience. Tis is likely to resultin a higher number of participants, as well as higher stickiness.

10. Marketing

If there's one thing that will get you more participants and more stickiness, it's good marketing. Yet academic institutions are often short of htese skills or see it as 'trade'. This is a big mistake. Marketing matters, it is a skill and need a budget.

Conclusion

The researchers at Derby used a very interesting phrase in

their conclusion, that “a certain amount

of chaos may have to be embraced”. This is right. Too many MOOCs are

over-structured, too linear and too like traditional University courses. They

need to loosen up and deliver what these newer diverse audiences want. Of course, this also means being

careful about what is being achieved here. Quality within these looser

structures and in each of these individual modules must be maintained.

Bibiography

Clark, D. (2013). MOOCs: Adoption

curve explains a lot. http://donaldclarkplanb.blogspot.co.uk/2013/12/moocs-adoption-curve-explains-lot.html

Hayes, S.

(2015). MOOCs and Quality: A review of the recent literature. Retrieved 5

October 2015, from http://www.qaa.ac.uk/en/Publications/Documents/MOOCs-and-

Quality-Literature-Review-15.pdf

Ho, A. D.,

Reich, J., Nesterko, S., Seaton, D. T., Mullaney, T., Waldo, J. & Chuang,

I. (2014). HarvardX

and MITx: The first year of open online courses. Re- trieved 22

September 2015, from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2381263

Leach, M. Hadi, S. Bostock, (2016) A. Supporting

Diverse Learner Goals through Modular Design and Micro-Learning. Presentation

at European MOOCs Stakeholder SummHadi, S. Gagen P. New model formeasuring MOOCs completion rates. Presentation at European MOOCs Stakeholder Summit.

You can enrol for the University of Derby 'Dementia' MOOC here.

And more MOOC stuff here.